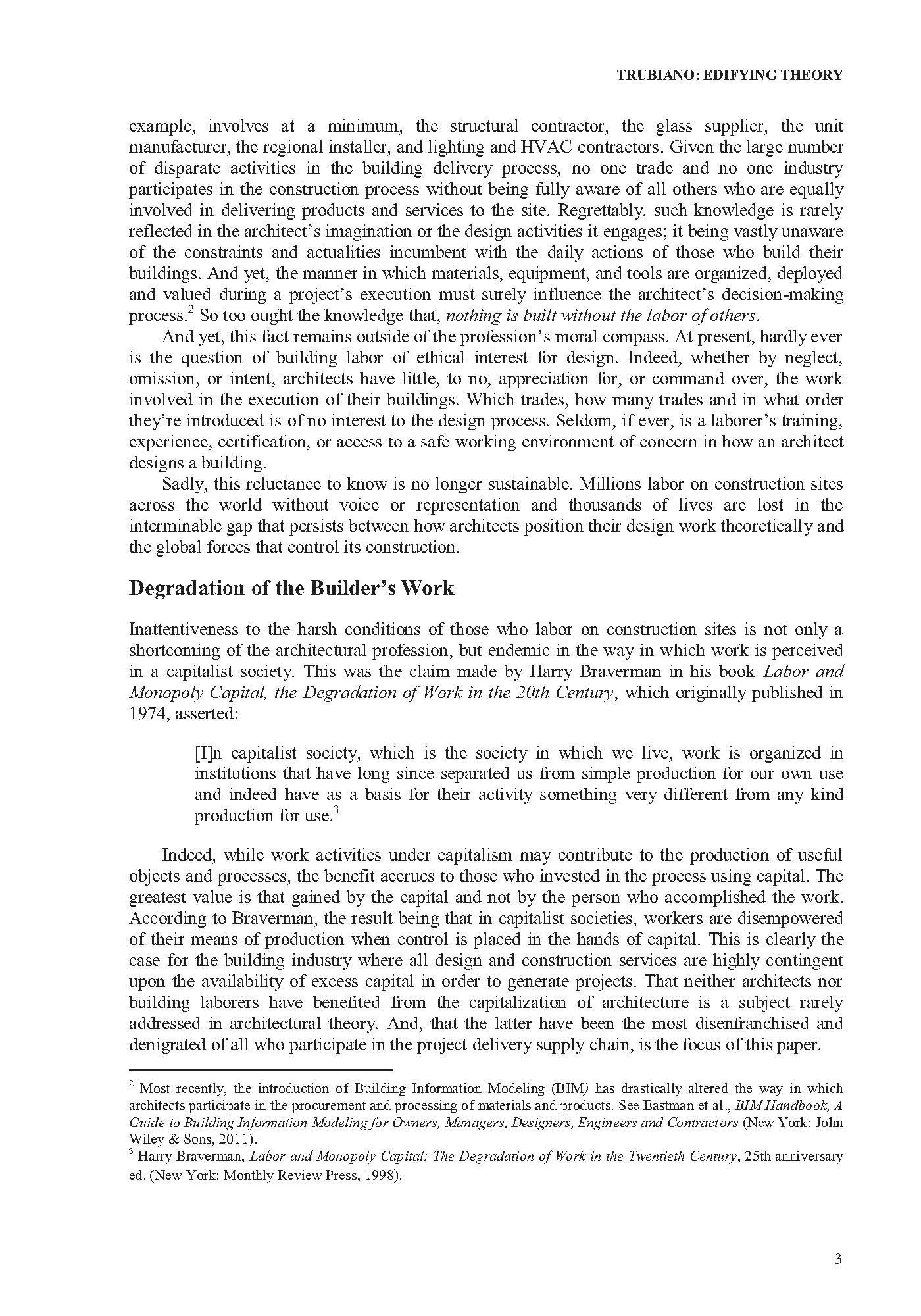

Shutterstock - Janabiya, Bahrain - October 20, 2017: Asian migrant workers plaster the facade of an apartment building on a scaffolding frame of a housing development in the Middle East.

By John Grummitt

Forced Labor, Urban Migration, and the Building Industry

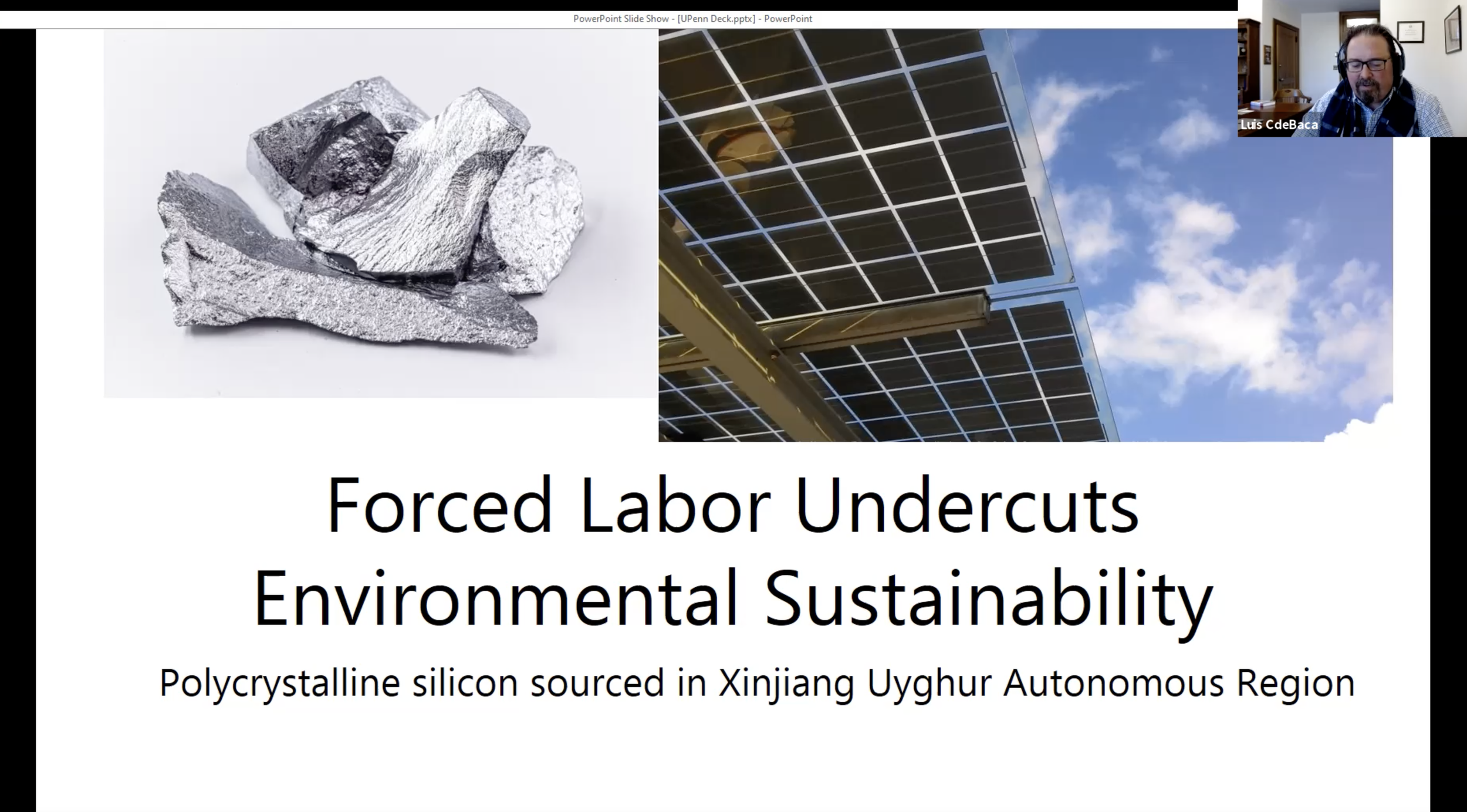

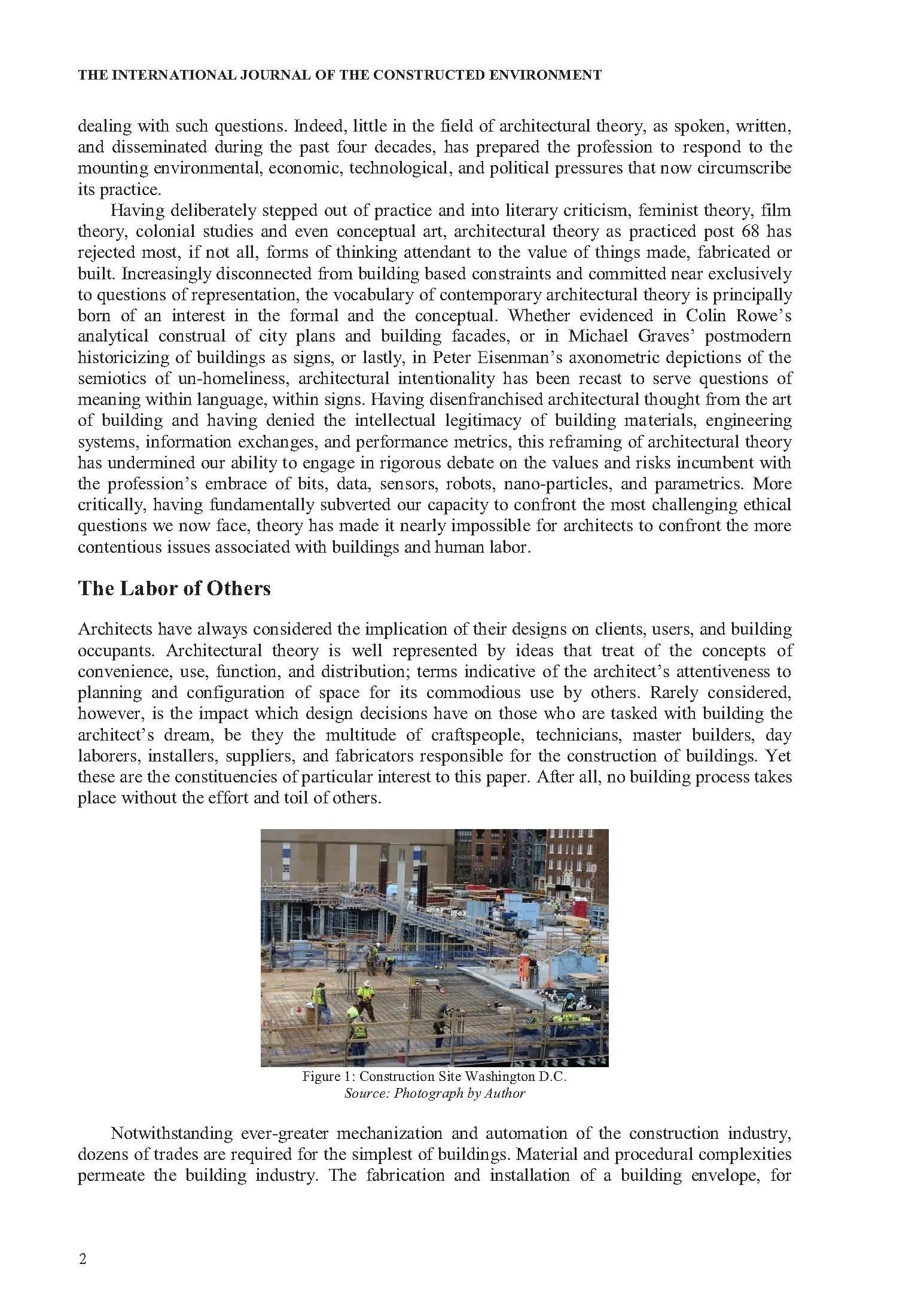

This project funded by the Perry World House (PWH) at the University of Pennsylvania aims to convene an international panel of building industry and labor experts, as well as policy makers working to address challenges and opportunities associated with eradicating forced labor in the globalized supply chain of buildings. In the twenty-first century, nearly every product introduced within the built environment is the result of an international supply chain of material and energy exchanges. That kitchen sink purchased from your favorite hardware store was possibly sourced from half a dozen countries, each with their own laws governing the extraction and manufacturing of materials, as well as the labor of those charged with its production. The aluminum, ceramic finish, rubber gaskets, and screws used in making the sink were most likely produced under different legislative jurisdictions. The same could be said for every doorknob, office desk, brick, carpet tile, concrete wall, glass window or shower tub fabricated, installed, and used by the public. Undoubtedly, the building industry is widely disparate and disaggregated; it is also one of the most under-resourced, under-researched, and underregulated. Those who labor in the extraction, manufacturing, and installation of building materials, are typically the most disempowered, disenfranchised, and at risk, and this because they are migrants. Examples of which, abound.

According to the CPWR - Center for Construction Research and Training (CPWR, 2010), barriers to wage equality, safety, and union entry persist for migrant Hispanic workers in the United States. They represent nearly fifty percent of all dry wall installers and concrete workers in the US, yet they remain voiceless and at increased physical risk. Work-related fatalities amongst Latino construction workers exceeds the proportion of their representation. They are the most vulnerable of laborers in the most hazardous of industries. According to investigators in “Migrant Work & Employment in the Construction Sector” (ILO, 2016), migrant construction workers, be they national or international, are regularly exposed to financial debt incurred while securing employment, physically strenuous working conditions on-site, sub-standard living conditions off-site, and lax immigration laws which do not expressly forbid indentured or forced labor. In South Africa, for example, where entry into the country is fairly easy, and where unemployment figures remain high, foreign workers are often arrested, deported, and even mistreated by law enforcement and employers.

As first studied during a H+U+D Mellon Fellowship Grant awarded in 2018-2020, the large-scale migration of low skilled laborers to urban centers accelerates the problem of forced labor in the construction industry. Indeed, migrant labor is the dark and dangerous underbelly of most rapidly developing cites. Ambitious construction projects continue unabated de- spite the international economic downturn of the early 21st century. The sheer quantity and magnitude of new cities, whether planned or built, carefully designed or informal, stupefies even the most jaded observer. And yet, urbanization at this scale is only possible with a migrant workforce of unskilled laborers who are called upon to toil on its building sites. Millions travel across the global in search of work in all sectors of the supply chain of materials and in the construction of buildings. This transnational displacement of vast numbers of humans in search of work contributes to a highly de-politicized body politic. And evidence only continues to mount that forced labor, kills.

The first set of on-line PWH workshops on Forced Labor, Urban Migration, and the Built Environment invited academics, designers, builders, lawyers, and policy makers to identify key challenges which must be addressed in service to this global community of material laborers. Participants included :

All sectors of building production and project delivery—from those who design, to those who commission, use, buy and sell, or pass laws that impact buildings—are called upon to acknowledge the significant ethical consequences supply chain slavery has on the larger communities they represent. This workshop seeks effective solutions, alternative strategies, and policy initiatives for repositioning the ethical compass of all who are involved in deciding the fate of millions of laborers who migrate every year in order to manufacture and build our ‘luxury’ environments. We are all called upon to assume responsibility vis a vis craftspeople, technicians, master builders, day laborers, installers, suppliers, and fabricators who struggle to work in just and safe environment. Indeed, by neglect, omission, or intent, designers, builders, lawyers and policy makers often have little appreciation for the struggles of those who build our homes, hotels, hospitals, and highways.

Forced Labor, Urban Migration, and the Building Industry will continue to host a diverse interdisciplinary group of experts working to increase transparency in the supply chain of building materials and construction labor, with the goal of influencing public policy and industry leaders. Let us know if you are interested in joining us !